This article reverse-engineers that painful journey. We will map the hidden cost structures behind “chip crunch”, audit the five failure points that kill timelines, and finish with a de-risking playbook any CTO can run in parallel with model training.

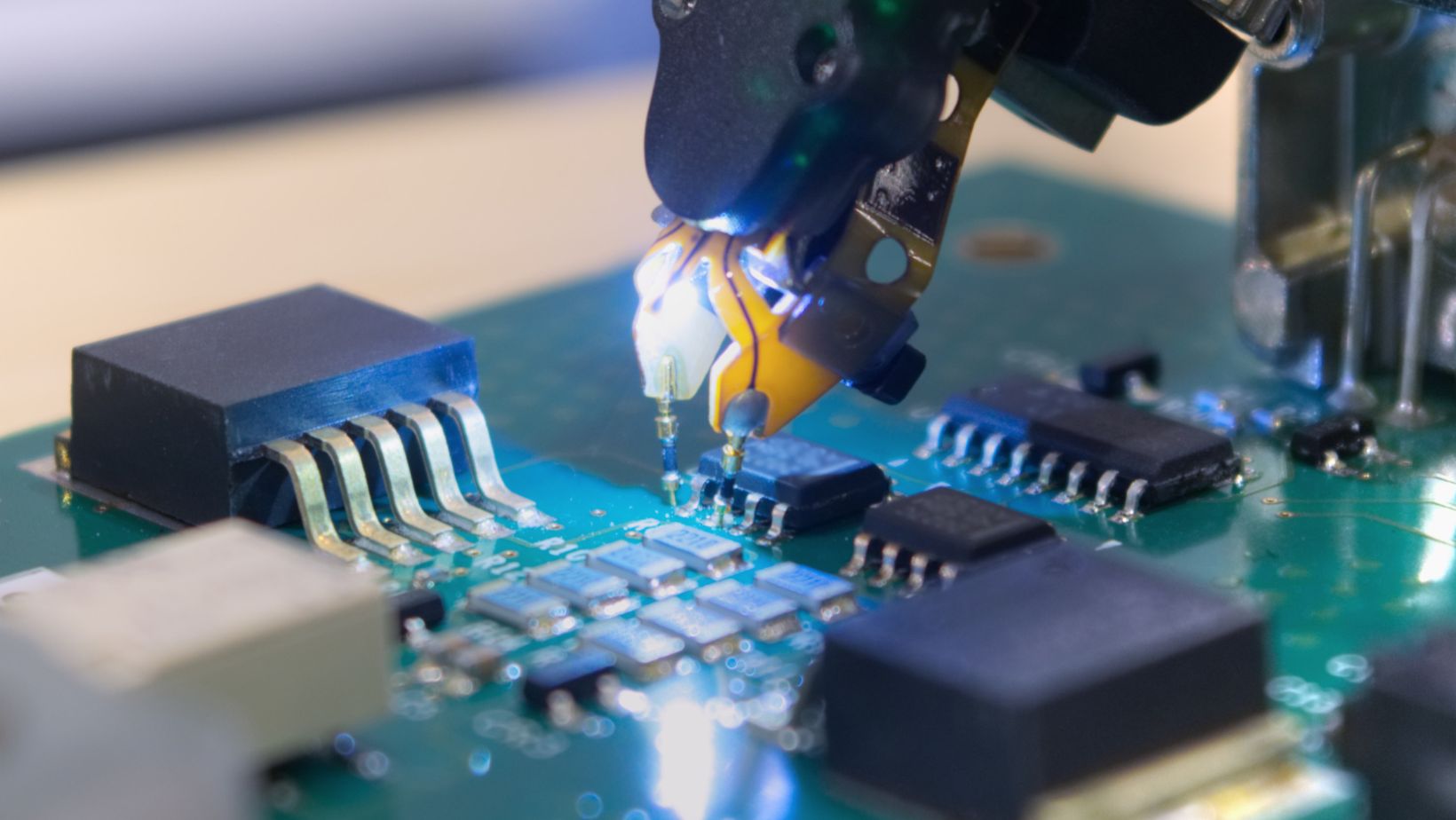

The Prototype-to-Production Reality Check

A vision-powered farming drone, built in a garage, might run perfectly on hobbyist boards. Raising seed funding usually triggers two irreversible decisions: a smaller, cheaper PCB and a production run the investors can touch. That’s when quotations from distributors replace slides from pitch decks—and when a 52-week lead time on a single sensor suddenly pits cash burn against calendar time.

ExpoSmall recently chronicled this phenomenon in “From Proof-of-Concept to Production: AI Deployment Gap Nobody Talks About”, noting that most AI proofs stall long before mass manufacture. Hardware is the missing bridge.

A Demand Tsunami Meets a Fragile Supply Base

More than half of chip-reliant organisations fear they won’t secure enough semiconductors in the next two years, while 81 % expect demand to rise another 21 % in just 12 months.

Three forces combine to make that prediction plausible:

- The GPU land-grab. Hyperscalers are buying data-centre accelerators at almost any price, starving smaller customers of allocation.

- Edge-AI gold rush. Laptops, routers and even espresso machines are getting neural-processing blocks, pulling mid-range fabs into record utilisation.

- Geopolitical fences. Export controls on advanced nodes reroute orders through limited foundry windows, amplifying the squeeze.

For a seed-stage company, these macro waves manifest as “allocation only”, “NCNR terms”, and one-line emails from suppliers: sorry, your ETA slipped another quarter.

Hidden Cost Structures: Where Timelines (and Cash) Evaporate

Global chip sales are forecast to hit US$697 billion in 2025, on track for the US$1 trillion mark by 2030.

That headline number hides a brutal skew: the revenue jump is driven by a narrow slice of high-end silicon. Everyone else competes for the same trailing-edge capacity—often on 90 nm processes older than some of their interns.

Why this matters to a startup:

- Per-unit cash drain. Small MOQ batches mean higher ASPs; every slip forces a new, more expensive quote.

- Currency of credibility. First orders rarely hit minimum economic scale, so early parts run on broker channels, raising quality-assurance costs.

- Runway algebra. A six-month delay on first revenue while payroll stays constant can halve survival time.

Five Failure Points Every AI Hardware Founder Must Audit

1. BOM Illusions vs. Real Lead-Time Data

Excel BOMs inherit the distributor lead times of the day they were downloaded. Reality changes weekly. Tie every line item to a live API feed.

2. Over-reliance on Single-Source Advanced Nodes

Your ASIC’s 5 nm tape-out is worthless if export rules change or the sole foundry is booked by cloud titans.

3. Regulatory & Export-Control Whiplash

A neural-processing unit that is ITAR-free today can become EAR-controlled tomorrow. Build alternative SKU options early.

4. Cash-Flow Squeeze from Minimum-Order Quantities

The cheapest MCU might force a 10 k purchase when you need 500 units. Model the cash impact before locking the schematic.

5. Talent Gaps in Supply-Chain Ops

Startups hire data scientists first and component sourcers last—yet those sourcers control the gating path to revenue. In many teams, this gap exists because talent planning happens in silos. A VP of AI recruitment who understands both technical depth and operational timing can prevent those mismatches before they slow production.

That velocity means component professionals have their pick of employers; waiting to hire them can be fatal.

A CTO’s Playbook: De-Risking Component Sourcing Early

- Split the BOM by criticality. Rank each part by replacement pain and create shadow part numbers for drop-in alternates.

- Adopt a dual-source policy above US$0.10. Even resistors can stall a build.

- Negotiate PPV buffers with investors. Price-purchase-variance reserves cut board-approval time when quotes rise.

- Escrow hard-to-find inventory. Specialist distributors like ICRFQ maintain in-house test labs and can warehouse small-batch parts under your name until production.

- Trigger DFx review at EVT, not DVT. Design-for-assembly tweaks—such as switching to commonly available capacitor sizes—save weeks later.

Sustainability & Investor Optics

- Nearly 60 % of downstream organisations now prioritise eco-friendly chip designs — same Capgemini survey as above.

Consolidating multi-vendor orders through a single hub (or stocking parts regionally) doesn’t just shrink freight emissions; it also satisfies LP due-diligence questionnaires increasingly focused on Scope 3 footprints.

The New Metrics Board Decks Will Ask For

- Lead-time variance (days) per top-20 components

- Allocation risk score (numeric blend of fab node, geography, and revenue share)

- De-risked gross margin after contingency buffers

Tracking these numbers monthly signals operational maturity—and surfaces risks before they appear in cash-flow statements.

Caveats & Counterpoints

Not every startup needs a custom board; some thrive by white-labelling reference designs, deferring the supply-chain quagmire. Others pivot to software-only licensing. That is a valid strategy—but the ceiling on valuation often tracks control over hardware IP. The company that solves sourcing early can expand into devices, appliances, even entire vertical stacks when the market opens.

Conclusion: Build Supply Muscle Before You Build Code

AI founders love fast feedback loops, yet hardware remains slow feedback by nature. Treat component sourcing as a core product function—staff it, fund it, dashboard it—and the next silicon squeeze can become your competitor’s problem, not yours.